WRITTEN BY: Corey Nelson

Article at a Glance

Industrial seed oils were invented when there was no meaningful health regulation, then became increasingly popular based on flawed research suggesting they were heart healthy.

In the intervening 100+ years, numerous in vitro cell studies, animal studies, human clinical trials, and observational studies have demonstrated the toxic effects of seed oils and their byproducts created during heating.

While there are a few possible benefits to seed oils, such as vitamin E, low amounts of omega-3 ALA, and reduction in cholesterol, according to some studies, these properties aren't unique to seed oils and don't outweigh the potential for harm.

Industrial seed oils are hard to avoid if you mainly eat food from restaurants and pre-packaged processed foods, but easy to avoid if you learn to read labels and do as much of your cooking as possible.

Introduction

Industrial seed oils, also known as vegetable oils, are in nearly everything. If you use common cooking oils, eat pre-packaged foods, or dine out at most restaurants, you’re probably eating them every day.

And you wouldn’t be alone — globally, vegetable oil production has increased more than 16-fold since 1909, has doubled in the last 20 years, and is expected to grow 30% in the next four years [*,*,*]. In the United States, the consumption of soybean oil alone has grown 1,000-fold since 1909 [*].

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that increased vegetable oil consumption correlates with higher rates of obesity, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and other modern health problems.

With so much evidence pointing to the harmful effects of seed oils, many have described them as “toxic.” But do seed oils meet the definition of toxicity?

In the hundred years since they first entered our diets, plenty of scientific findings suggest that seed oils have toxic effects on cells, animals, and humans. Abundant evidence also suggests they're likely unsafe for long-term consumption in quantities most people eat today.

In this article, you’ll get a firsthand look at all the evidence so you can decide what you think for yourself. We’ll rigorously examine the issue of seed oil toxicity, starting with defining terms, then looking at a variety of studies that clarify the safety of seed oils, as well as reconciling conflicting evidence.

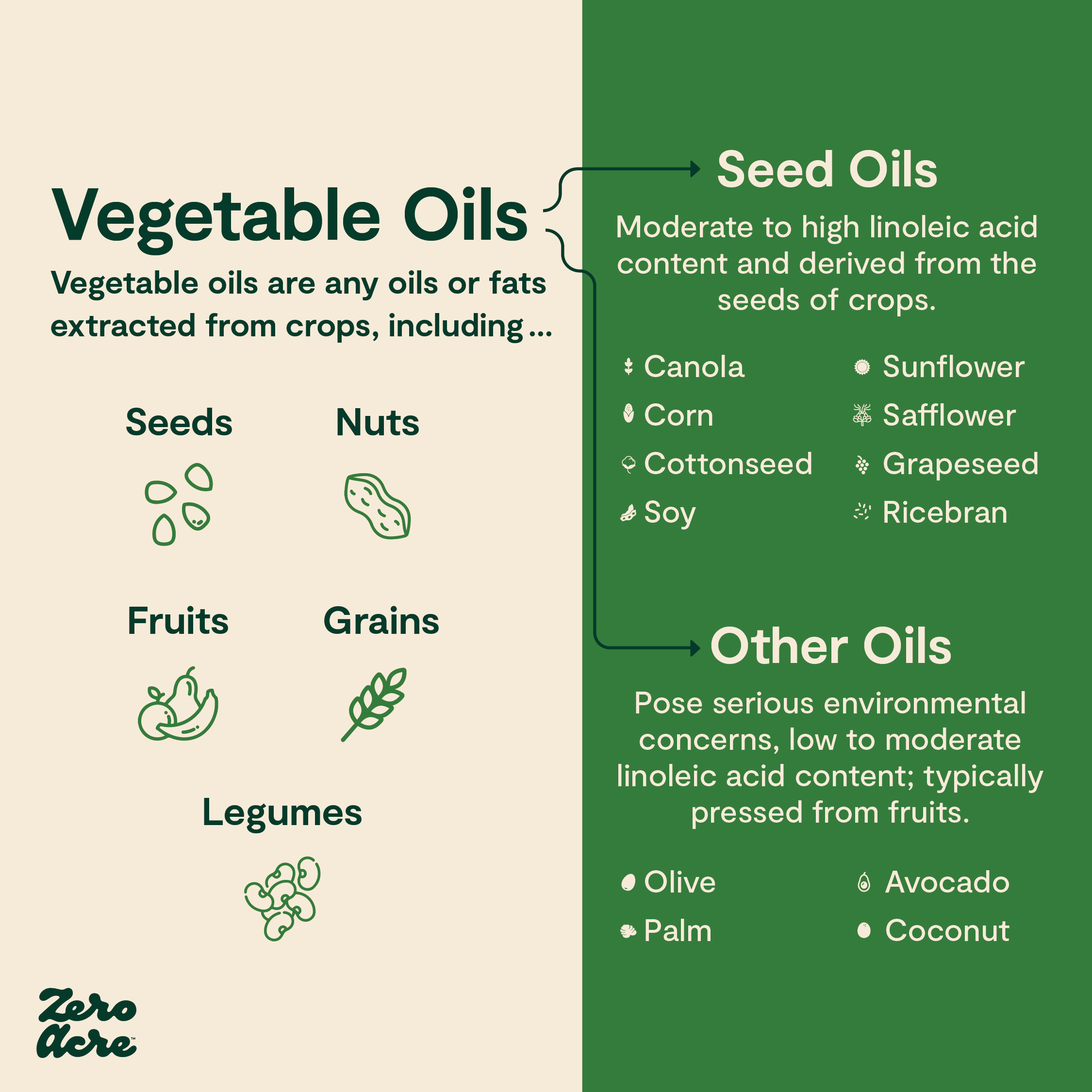

But first, what are vegetable oils exactly? And are seed oils different?

Seed Oils vs. Vegetable Oils: What Are They?

The terms “vegetable oil” and “seed oil” are often used interchangeably but actually have different meanings. To explore what the best evidence says about seed oils' safety and possible toxicity, we'll need to start by defining each term.

Vegetable oils are any oils or fats derived from crops, including fruits, grains, nuts, and seeds. This is a broad category that includes all crop-based oils.

Seed oils, also called industrial seed oils, are a particular category of vegetable oils that are derived from seeds. “Vegetable oil” isn’t a very accurate description or a helpful way to think about them — these oils aren’t exactly pressed from kale or broccoli.

Instead, seed oils are refined from the seeds of crops, often using industrial methods including solvents, high heat, and large amounts of mechanical pressure. And that’s one reason they’re a relatively recent addition to the human diet: before large-scale industrial manufacturing and processing, it simply wasn’t a viable option to produce many seed oils or add them to foods.

Here are the most common examples of industrial seed oils to keep in mind:

Canola (rapeseed) oil

Corn oil

Cottonseed oil

Grapeseed oil

Peanut oil

Rice bran oil

Safflower oil

Soybean oil

Sunflower oil

Not only is seed consumption at such a massive scale new to the human diet, but all of these oils are also high in an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (or PUFA) called linoleic acid [*].

Omega-6 fats, while necessary in extremely small amounts, contribute to general inflammation and other health issues when eaten in excess [*,*]. That’s why many of the health impacts of seed oil consumption are similar despite varying types of seed oils in different diets.

Although people certainly ate foods like corn, peanuts, and sunflower seeds before industrial seed oils became available, it wasn’t feasible to get such significant quantities of linoleic acid through whole foods in the past. In 2017, people living in industrialized countries consumed 20% or more of their calories from seed oils high in linoleic acid, reflecting a 20-fold increase in seed oil consumption in the past 100-120 years [*].

Industrial seed oils also tend to contain fats that are oxidized or structurally damaged at the molecular level [*]. This isn’t their natural state but rather occurs from industrial processing, during storage, or when they’re heated and used for cooking.

In fact, oxidation is a critical factor that makes the biological effects of seed oils significantly more harmful than other fat sources that aren’t as easily oxidized [*]. In other words, consuming industrially processed sunflower oil is much different than eating whole sunflower seeds.

Finally, when we discuss seed oils for the purposes of toxicity, we’re not including olive oil, avocado oil, or coconut oil. Compared to most seed oils, these fruit oils have only low to moderate amounts of linoleic acid. For example, whereas sunflower seed oil contains up to 75% linoleic acid, olive oil averages around 12% linoleic acid, with levels ranging up to about 27% [*,*,*].

Are Seed Oils Toxic?

Current data suggest that “toxic” is an appropriate word to describe high linoleic seed oils, especially when heated, and especially in the amounts most people consume them today — an increase from 1-2% of to 6-10% or higher over the last hundred years [*,*].

While the basic medical definition of toxicity may seem to set a high bar for referring to seed oils as “toxic,” there are other elements to keep in mind besides acute toxicity.

Toxicity isn’t only acute, it’s also directly dependent on the amount and concentration of a substance taken over time — hence the saying “the dose makes the poison” [*].

For example, artificial trans fats won’t kill you with a single serving but are considered toxic because they significantly increase the risk of heart attack and stroke when included as part of your regular diet [*]. Trans fats are considered so harmful they were recently banned from food in the United States, Brazil, and Europe.

Similarly, exposure to toxic chemicals found in secondhand tobacco smoke is associated with around 34,000 deaths of nonsmokers from heart disease each year in the U.S. alone — but only with repeated exposure over time [*,*].

So, when we talk about toxicity, it’s essential to keep in mind an organism’s individual response and whether a chemical or substance is taken alone or together with other, different chemicals or substances.

Toxicity can occur systemically (to the entire body) or locally (in only one area or organ system), be reversible or nonreversible, and occur all at once (acutely) or over time (chronically).

In other words, toxicity doesn’t only refer to substances that are harmful enough to immediately kill you outright. A substance that causes enough harm over time, even when it’s not the only cause in a given case, can also count as toxic.

Are Seed Oils Safe?

According to Merriam-Webster, the basic definition of safety is “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss” [*].

Proving a food or drug is unsafe or safe is actually different from showing that it’s toxic or conversely, doesn’t meet the definition of toxicity.

Toxicology studies mainly focus on escalating the dose of a substance higher and higher until harmful effects appear. In contrast, safety studies look for low-grade toxic effects that occur over time with lower doses. In addition, safety studies focus on using amounts that are more typical of how the substance would be ingested or used.

In other words, it’s easier for toxicity studies to give a black-and-white answer as to whether a substance is acutely dangerous and in what quantities. On the other hand, safety studies contain more shades of gray because they tend to look for subtler effects that aren’t immediately dangerous or fatal.

Now, before we dive into the body of scientific evidence that’s accumulated on seed oils during the last hundred years, here’s a quick refresher on the regulatory environment that led to the creation of seed oils in the first place.

Seed Oils, Health Claims, and Regulation

Today, new food ingredients and pharmaceutical drugs undergo testing, clinical trials, and other safety checks before being sold for human consumption.

Regulators and safety experts apply various criteria for the safety of prepared food versus food ingredients versus drugs, and so on. The usual progression for novel substances goes from in vitro cell toxicity studies to animal studies, and finally, for substances that pass these trials, smaller and then more extensive human studies and clinical trials.

On the other hand, foods and ingredients that have been used by enough people, or have been around long enough, can be approved for use without a formal premarket approval process based on their past usage [*].

When this occurs, a food or ingredient deemed safe is given the official designation generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the U.S. FDA or equivalent in other countries [*].

The first industrial seed oils made their way into modern diets in the late 1800s, and the first mass-market seed oil sold for human consumption in the early 1900s was Crisco, which is a form of hydrogenated seed oil [*].

Even though the first industrial seed oils had vocal critics — the magazine Popular Science wrote that “What was garbage in 1860 was fertilizer in 1870, cattle feed in 1880, and table food and many things else in 1890” in reference to them — health claims were unregulated [*].

The first nationwide consumer protection law in the U.S. was the Pure Food and Drug Act, passed in 1906. As its name suggests, the main focus was on misbranded, adulterated, and contaminated foods, so the safety of seed oils was outside of its scope (as long as these products were labeled accurately as to their contents, unregulated health claims aside).

In other words, seed oils entered into usage during a time of minimal food regulation. The concern was whether these products were being labeled accurately — not whether they were fit for human consumption in the first place.

The modern FDA wasn't established until the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, and the first version of today’s GRAS list came into being in 1958.

For reference, here’s when the most common seed oils entered into mass industrial production for human consumption:

Corn oil: 1898-1899 [*]

Cottonseed oil: late 19th century [*]

Peanut oil: 1930s [*]

Safflower oil: 1940s [*]

Refined soybean oil: mid-20th century [*]

Refined sunflower oil: 1946 [*]

As you can see, most of these oils automatically meet the criteria to be generally recognized as safe (GRAS) on the basis of their widespread use before 1958.

One surprising exception is canola oil, first produced in Canada in 1974 [*]. The term canola oil, short for "Canada oil, low acid," turned out to be more marketable than its original technical name: low erucic acid rapeseed oil.

Canola oil was widely adopted immediately by the food industry, then granted GRAS status in decisions in 1977 and 1985 because regulators deemed that it had already been in wide enough use to merit a safety pass [*,*].

The GRAS decisions for canola oil have focused on its chemical composition, fatty acid profile, heavy metal risks, and potential allergens [*,*].

While these factors are important for understanding the acute toxicity risks, the picture that emerges is that canola and other seed oils never underwent rigorous safety testing for premarket approval.

That ship has sailed, but what does the science that’s emerged since their widespread adoption have to say about their toxicity and safety? Let’s start with cell studies and work our way up to human trials.

In Vitro Cell Studies on the Toxicity and Safety of Seed Oils

Cell studies — done on living cells but in a laboratory setting, outside of organisms — are the simplest and most direct way to study toxicity.

But keep in mind that the scientific definition of toxicity relies on defining the dose and circumstances of exposure. So while in vitro (“within the glass,” referring to a test tube, even though a test tube may not be the literal vessel) studies can provide helpful insights, they provide an incomplete picture of real-world safety.

To investigate the safety of a substance, scientists usually start with in vitro toxicity studies that compare the effects of a new substance to known or accepted ones before moving to animal studies or human clinical trials. This form of evidence can also provide helpful insight in light of future, more complex safety studies.

Linoleic Acid and Immune Cells

A 2004 cell study comparing the effects of bathing T lymphocyte cells in a high concentration of either linoleic acid or oleic acid (an omega-9 fatty acid found in olive oil and many other foods) found that linoleic acid caused immunologically harmful effects [*].

The authors expressed concern that seed oils high in linoleic acid could be immunosuppressive and may harm the immune function of critically ill patients when given as part of hospital nutrition, which is a common practice via soybean oil added to nutritional formulas.

The same group repeated a similar study in 2006 and found, once again, that linoleic acid was much more toxic to human lymphocytes compared, and that it killed cells by producing ROS (radical oxygen species, also called free radicals) and preventing mitochondria from producing energy [*].

A different group of scientists also conducted a 2005 study with similar results [*].

Linoleic Acid and Retinal and Immune Cells

In 2021, after observing increased linoleic acid levels in the feces of patients with acute anterior uveitis (severe eye inflammation), researchers examined the effects of linoleic acid in retinal cells and several types of immune cells [*].

The study found that linoleic acid inhibited the function of human and mouse immune cells called dendritic cells and T helper cells, caused cell death in human dendritic cells, and decreased the functioning of retinal pigment epithelial cells.

Two studies from 1996 and 2000 also found that linoleic acid is highly toxic to cells from cows’ eye lenses, known as bovine epithelial lens cells [*,*].

Linoleic Acid and LDL Cholesterol Oxidation

Research suggests that oxidation (structural damage) in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol strongly contributes to developing atherosclerosis (a form of cardiovascular disease) — with some scientists going so far as to say that atherosclerosis can’t occur without oxidized LDL [*].

In a 1993 experiment, researchers measured the rate and extent of LDL oxidation from patients as it related to the content of oleic acid and linoleic acid found in their cholesterol [*].

The researchers found that higher levels of oleic acid and lower levels of linoleic acid helped to prevent LDL oxidation and vice versa — that lower levels of oleic acid and higher levels of linoleic acid increased rates of LDL oxidation.

Linoleic Acid and Insulin-secreting Cells

A 2006 cell study comparing the toxicity of various fatty acids to RINm5f cells, a line of rat insulin-secreting cells used in experiments, found that linoleic acid and palmitic acid (a common saturated fat found in palm oil and to a lesser extent in meat and dairy) caused greater plasma membrane loss and DNA fragmentation compared to oleic acid, stearic acid, and omega-3 EPA [*].

These findings in insulin-secreting cells may be relevant to the effects of seed oils on people at risk of diabetes and people who have diabetes — a theme we'll examine further in animal and human studies shortly.

Linoleic Acid and Reproductive Germ Cells

A 2010 study examining the effects of linoleic acid supplementation on bovine oocytes (immature egg cells from cows) found that the omega-6 fat interfered with the maturation of the cells and inhibited early embryo development [*].

According to the study authors, this evidence suggests that linoleic acid in follicular fluid is likely associated with the declining fertility rates documented in farm animals and as well as in humans, both of which are consuming more linoleic acid than ever before.

In 2016, a different research group conducted a study using similar methods and found the same results [*].

Animal Studies on the Toxicity and Safety of Seed Oils

For new substances (including pharmaceutical drugs and new dietary ingredients), scientists most often move to animal studies after doing preliminary studies in cells.

Studies on animals allow for a better understanding of toxicity and safety compared to cell studies, but are less expensive compared to human studies. They’re also another early opportunity to identify when a substance is toxic or unsafe, in which case researchers would avoid progressing to human trials.

In this section, we’ll cover a variety of animal studies looking at the effects of seed oils and linoleic acid on atherosclerosis, the brain, metabolism and obesity, and cancer.

Linoleic Acid and Atherosclerosis

In a series of experiments published in 2002, scientists fed groups of mice oxidized linoleic acid byproducts, which result from normal heating of linoleic acid during cooking [*]. They found increased oxidative stress (cellular damage) and larger cardiovascular lesions in most of the mice given the oxidized byproducts.

In a 2017 experiment, mice receiving a mere 9 or 18 milligrams per day of oxidized linoleic acid had lower levels of liver ppar-alpha (a change associated with fatty liver, impaired glucose metabolism, and metabolic issues) and lower plasma levels of HDL ("good cholesterol") [*].

While previous studies have shown oxidized LDL can lower triglycerides, which some researchers consider positive for cardiovascular health, these researchers concluded that longer-term oxidized linoleic acid consumption could lead to atherosclerosis.

Linoleic Acid, Neurological Development, and Alzheimer’s

In a 2008 animal study, researchers raised the question of whether current high omega-6 fatty acid intake is contributing to poor neurodevelopment in young humans.

This study on young piglets provided two different diets designed to investigate the effects of early infant nutrition: one with required amounts of linoleic acid to prevent deficiency (1.2% of overall calories) versus another with high amounts (10.7%, which is equivalent to modern human intakes) [*].

The low-intake group had healthy, normal brain development, but the group consuming linoleic acid levels of 10.7% of overall calories had impaired and altered neurological development [*].

And in a 2017 study using mice predisposed to developing characteristics of Alzheimer's, researchers gave mice regular chow or chow supplemented with canola oil, which increased dietary linoleic acid, for six months [*].

The study showed that increasing linoleic acid intake led to a significant increase in body weight, impairments in working memory and brain structure, and more beta-amyloid plaque development (which is associated with developing Alzheimer’s disease in humans) compared to the control group.

Linoleic Acid, Metabolism, and Obesity

A 1993 study found that in rats eating standardized diets that contained either safflower oil (high in linoleic acid), olive oil, or edible tallow as an additional fat source, the rats consuming the most linoleic acid gained approximately 16% more weight compared to the olive oil group and 36% more weight than the tallow group — even though all rats received the same overall caloric intake [*].

In a 2012 mouse study, researchers hypothesized that elevated linoleic acid would promote obesity through overactivation of the endocannabinoid system [*].

They designed their experiment to model "20th-century increases of human LA consumption, changes that closely correlate with increasing prevalence rates of obesity," and found that higher linoleic acid intakes did increase food intake and fat storage. However, reducing linoleic acid reversed these effects in the mice.

In a 2017 experiment, researchers divided male mice into groups receiving a low-fat diet or a high-fat diet containing 1%, 15%, or 22.5% of calories from linoleic acid, with the rest from saturated fat [*].

Compared to both the 1% linoleic acid group and the low-fat diet, rats receiving the 22.5% linoleic acid diet had:

Greater body weight gain

Decreased activity levels

Heightened insulin resistance

The authors concluded that "in male mice, LA induces obesity and insulin resistance and reduces activity more than saturated fat, supporting the hypothesis that increased LA intake may be a contributor to the obesity epidemic."

A separate 2019 study found that when mice were given a diet with 8% linoleic acid for eight weeks, their body weight increased significantly compared to a group given 1% linoleic acid. Mice consuming more linoleic acid and more glucose together consumed more calories and gained more weight for the number of calories consumed than the other groups [*].

In a 2015 study, researchers gave young rats a control diet with 3.16% of energy from linoleic acid or a "low LA" diet with 1.36% of energy from linoleic acid [*].

They later switched all the animals to a Western-style diet and monitored body composition, blood sugar, and other variables. Unsurprisingly, the "low LA" group accumulated 27% less fat from the Western diet and had lower triglycerides, suggesting that decreasing linoleic acid intake early in life may help prevent obesity and metabolic problems later.

Linoleic Acid and Cancer

While there are no well-designed long-term human trials on the effect of dietary linoleic acid and cancer outcomes, this omega-6 fatty acid does promote tumor growth in some animal studies and is linked to breast cancer and lung cancer in observational studies.

Study findings include:

Human Clinical Trials and Observational Studies on the Toxicity and Safety of Seed Oils

Now that we've examined cell and animal studies in-depth, it's time to look at existing human evidence on the toxicity and safety of seed oils.

Unfortunately, unlike most safety studies done on foods and drugs, the majority of early human seed oil studies weren’t designed to look for harm caused by consuming linoleic acid and seed oils.

Instead, most of the high-quality human clinical study data suggesting seed oils could be harmful actually came as a surprise — even to the scientists conducting the research. And in some cases, the controversial aspects of research pointing to seed oil harm remained intentionally unpublished for decades, only coming to light recently[*].

Although the suppressed evidence may have skewed decades of public policy and health outcomes, fortunately, there’s a renewed and growing interest in examining this issue today.

Let’s take a look at nearly 60 years of human safety findings on seed oil and linoleic acid, from the 1960s to the present.

Oxidized LDL as a Risk Biomarker for Cardiovascular Disease

In a 2017 study, researchers examined LDL cholesterol samples in 42 men with coronary artery disease compared to a control group of 40 men without coronary artery disease [*].

They found that men with coronary artery disease had a significantly different LDL cholesterol composition, which included higher levels of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid, an inflammatory byproduct of linoleic acid. Their cholesterol was also significantly more oxidized (structurally damaged), which the study authors concluded was most likely due to its linoleic acid content.

Older heart disease research mainly focused on LDL cholesterol levels as a risk marker, but newer research strongly suggests that the amount of oxidized LDL is a better predictor of cardiovascular problems [*, *, *].

More dramatically, new research from 2021 suggests that atherosclerosis might not even be possible without oxidized LDL cholesterol [*].

The Effect of Lowering Dietary Linoleic Acid on Oxidized Metabolites

When you eat a lot of linoleic acid, it not only affects the makeup of your cholesterol, but also affects the structure of various tissues throughout your body.

As we’ve discussed, linoleic acid is inherently unstable, meaning that it oxidizes and breaks down into other compounds — and these compounds are even more inflammatory and damaging than linoleic acid [*].

These processes occur during the industrial manufacturing and high-heat cooking of omega-6 seed oils and can also occur within your body when you eat fats high in linoleic acid [*].

The four byproducts that have been studied most thoroughly are:

9-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE)

13-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE)

9-oxo-octadecadienoic acid (9-oxoODE)

9-oxo-octadecadienoic acid (13-oxoODE)

These byproducts are not only closely linked with cardiovascular disease — for example, they're 20 times more abundant in the LDL of patients with atherosclerosis compared to controls — but they’re also associated with other conditions, including chronic pain, Alzheimer's dementia, and fatty liver disease [*,*].

In a 2012 trial, researchers measured levels of these four linoleic acid byproducts in chronic headache patients before and after a 12-week diet low in linoleic acid, from a median baseline (pre-study) intake of 6.74% of daily calories reduced to 2.42% of daily calories during the study [*].

They found that the diet lower in linoleic acid significantly reduced linoleic acid byproducts as well as dramatically reduced several measures of chronic headaches and pain and increased quality of life compared to the control group [*].

These results show that reducing linoleic acid in your diet can quickly reduce harmful, inflammatory compounds in your body. The implications aren't only crucial for people with headaches but also for preventing the many other conditions associated with linoleic acid byproducts, including heart disease and dementia.

Linoleic Acid Studies Showing Increased Rates of Cardiovascular Death or Death from All Causes

The Minnesota Coronary Experiment, conducted on 9,423 institutionalized men and women from 1968-1973, was a double-blind, randomized controlled trial designed to understand the effects of replacing saturated fat with corn oil and corn oil-based margarine rich in linoleic acid [*].

While the group receiving seed oils had a significant 13.8% reduction in cholesterol compared to only 1% reduction for the control, there was no reduction in deaths for the control group and no benefit for atherosclerosis or heart disease [*].

Worst of all, a regression analysis shows that the risk of death increased by 22% for each 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L) reduction in serum cholesterol, which suggests that instead of the expected benefits of seed oil consumption, the opposite occurred and compliance with the high linoleic acid diet likely increased the risk of death in spite of cholesterol reduction [*].

The Rose corn oil study was a small 1965 trial of 54 participants with heart disease that randomized people into a group that received daily doses of corn oil, olive oil, or a control group [*].

The subjects were instructed to consume 80 grams of oil per day, but researchers realized most people were unable to achieve this dose. Instead, they told participants to take as much as they could, and estimated intakes fell to around 48 grams per day.

At the two-year mark, the rate of cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks, had nearly doubled in the corn oil group, and their cumulative risk of death was over 3.5 times higher. Some patients were also withdrawn from the trial early because they developed glucose in their urine (glycosuria), a symptom of diabetes, which resolved after stopping corn oil consumption.

Although the Rose corn oil study was relatively small, its results are consistent with many other in vitro and animal studies.

Another well-known study with similar outcomes was the Sydney Diet Heart Study, conducted from 1966 to 1973 with 458 men aged 30-59 who had experienced a recent coronary event [*].

The men were randomized into either a group that replaced dietary saturated fats with high linoleic acid safflower oil and safflower oil-enriched margarine, or a control group that received no special dietary instructions.

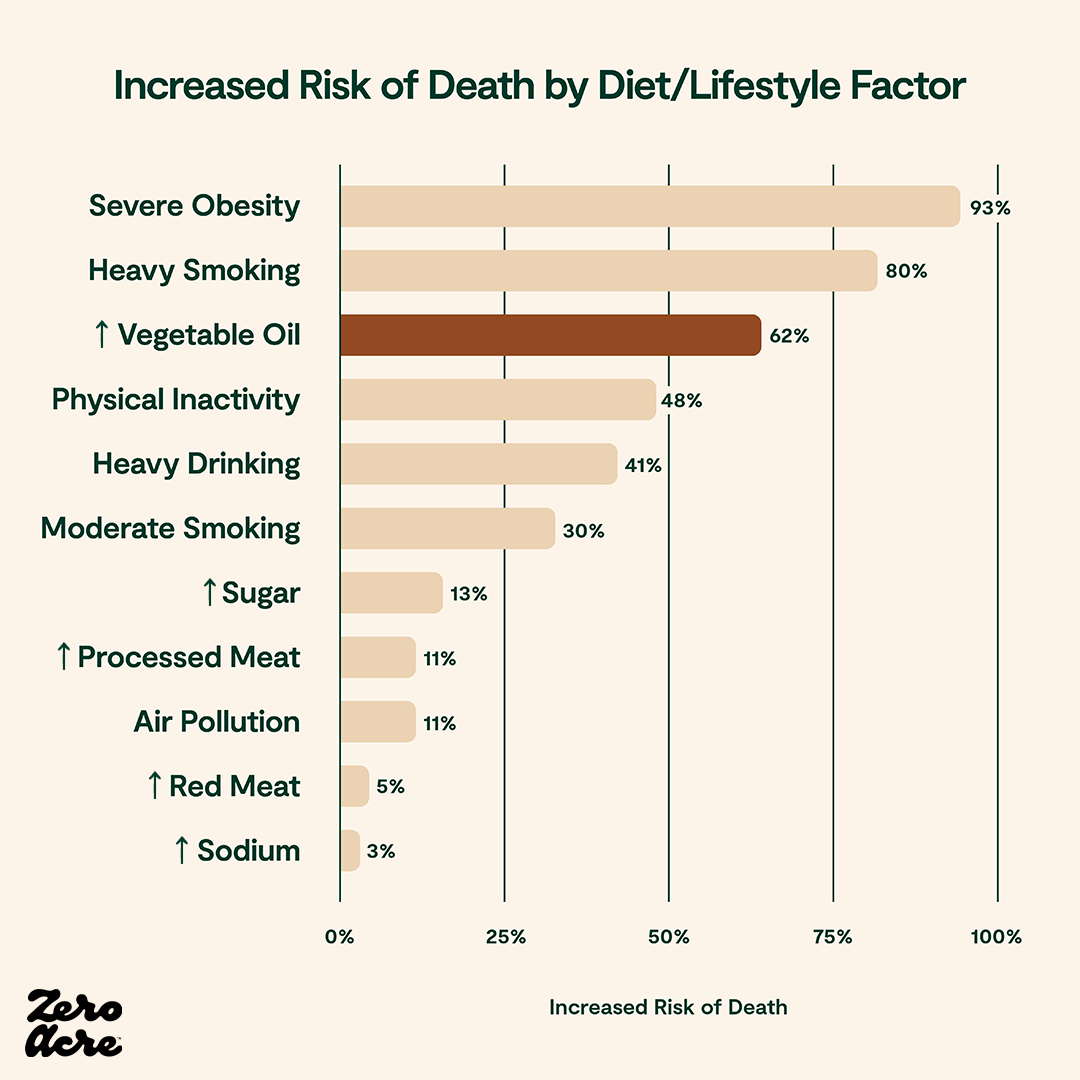

The intervention group consuming more linoleic acid had a 5.8% higher absolute risk (49% relative risk increase) of death from all causes, 6.2% higher absolute risk (56% relative risk increase) of cardiovascular disease, and 6.2% higher absolute risk (62% relative risk increase) of coronary heart disease compared to the control group.

To put this into perspective, the only diet and lifestyle factors that were found to be more dangerous than increased vegetable oil consumption were heavy smoking and severe obesity.

↑ = Increased consumption of; Severe obesity: BMI 35–40 [*]; Heavy smoking: ≥10 cigarettes/day (avg 21.97 or ~1 pack) [*,*]; Vegetable oil: Increase consumption by 12% of calories [*]; Physical inactivity: <2 times/week [*]; Heavy drinking: >14 drinks/week for men or >7 drinks/week for women [*,*,*]; Moderate smoking: <10 cigarettes/day [*]; Sugar: ≥73.2g sugar/day for women or ≥79.7g sugar/day for men [*]; Processed meat: Increase of at least 2 servings/week [*,*,*]; Air pollution: per 10 μg/m3 long-term exposure to PM 2.5 [*,*]; Red meat: Increase of at least 2 servings/week [*,*,*]; Sodium: >2,300 mg/day [*]

Keep in mind that these studies were designed to demonstrate the benefits of seed oil consumption, not to investigate potential harm from a high linoleic acid diet. As a result, the authors downplayed their findings at the time, which we’ll come back to shortly.

Present-day health statistics might look quite different if objective, balanced safety research on dietary linoleic acid from seed oils had been conducted and published in the 1960s and 1970s.

Higher Incidence of Cancer-Related Death

In the 1960s, the American Heart Association conducted an eight-year clinical trial on over 800 veterans living in Los Angeles to examine the effects and potential benefits of a diet high in polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), particularly linoleic acid, for middle-aged and older men [*].

The high PUFA group consumed 38% of total fat intake from linoleic acid versus 10% for the control group. This equates to 14.8% or 3.9% of total calories, respectively — that is, 369 calories per day coming from 41 grams of linoleic acid for the high PUFA group, and 97 calories coming from just under 11 grams per day of linoleic acid for the control group.

The researchers also measured the linoleic acid levels of adipose tissue (stored body fat) and found that in people following the high linoleic acid diet, it increased from a baseline of 10.9% to 33.7% over about five years.

Unfortunately, the study had several flaws, including:

Twice as many smokers in the control group (and yet, despite this fact, the control group that received lower linoleic acid intake still died less)

Much higher omega-3 intake in the high PUFA experimental group

Higher vitamin E intake in the experimental group and elevated vitamin E deficiency rates in the control group

Increased intake of harmful trans fats in the control group compared to the experimental group

More participants with past heart attacks and other cardiovascular problems in the control group

Regardless of these between-group differences and a 13% reduction in cholesterol measured in the experimental group, the study still failed to demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of the high linoleic acid diet for fatal atherosclerotic events and found “little difference in total mortality rates” between the groups.

Perhaps most concerning, though, was an increased rate of death by cancer documented in the experimental group. The participants eating more calories from linoleic acid were 82% more likely to die from cancer compared to the control group — even though half as many of them smoked and they ate more omega-3s and vitamin E and fewer trans fats, all of which would otherwise be predicted to result in a lower incidence of cancer.

Inhaled PUFAs from Cooking Fumes and Cancer Risk

You may have heard that it's important to use cooking oils with a high smoke point because burning fats increases oxidized (damaged) byproducts in foods. And this damage is associated with inflammation, cancer, and heart disease. (This is especially true of linoleic acid and other omega-6 fatty acids, as we already covered in some previous sections in this article.)

Along with burned oils being unhealthy to ingest, cooking fumes are also harmful to breathe in. This is why many building codes, especially for restaurants, require range hoods and other forms of kitchen ventilation.

A meta-analysis of over 9,500 nonsmoking Chinese women found that over time, increased exposure to these fumes could increase the risk by 74-111% — in other words, potentially more than doubling the rate of lung cancer [*].

These fumes mainly contain two types of chemical compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and aldehydes, both of which are carcinogenic and higher in PUFAs compared to other forms of fat [*,*].

A computerized model study found that compared to monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and saturated fatty acids (SFAs), linoleic acid and other polyunsaturated acids (PUFAs) generated 300% higher levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) during cooking at high temperatures [*].

Ultimately, it's good to minimize your exposure to all cooking fumes with proper ventilation and also by using oils with low PUFA content and high smoke points for cooking.

Are There Seed Oil Benefits?

Aside from economic and financial reasons (seed oils are an extremely cheap source of fat that adds flavor and texture to food), one of the biggest reasons for seed oils’ rise in popularity was the belief that they were good for you. But how accurate are these claims based on current scientific evidence?

While it's true that some studies show potential health benefits of seed oils, many of these are flawed. And as we’ve seen from numerous studies and trials, there is strong, non-circumstantial evidence that seed oils can be extremely harmful.

For instance, there’s proof that the 20th-century view that linoleic acid reduces cardiovascular risk was based on incomplete data sets and flawed interpretations.

As we saw with the Minnesota Coronary Experiment and the Los Angeles veterans study, increasing linoleic acid often does reduce LDL or total cholesterol, but remarkably, it does so without the predicted benefit on cardiovascular disease and mortality.

The reason for this disparity in interpretations is that the prevailing belief for much of the 20th century was that lowering cholesterol must result in reduced risk. Now we know that oxidized LDL is a better independent predictor of heart disease, so it makes perfect sense that linoleic acid could lower cholesterol levels yet increase heart disease and death via another mechanism: by increasing the oxidation rate of cholesterol (among many other mechanisms, as we've covered).

In fact, today, there are over 8,000 papers investigating the link between atherosclerosis and the oxidation of LDL [*].

Plus, any possible redeeming qualities of industrial seed oils aren’t unique. While many contain vitamin E and alpha-linoleic acid (ALA, a form of omega-3), there are plenty of great food sources of these nutrients that don’t contain harmful linoleic acid. They’re also much more stable and bioavailable.

And while linoleic acid is an essential fatty acid (EFA), required levels are closer to the pre-1930s intake 1-2% of total calories per day, not the 6-10% or higher average intake documented today [*].

It’s highly unlikely that anyone is deficient in linoleic acid these days, and there are plenty of ways to get healthy amounts of dietary linoleic acid without consuming harmful oxidized linoleic acid from seed oils.

For example, according to the United States Department of Agriculture:

An ounce serving of almonds contains over 4 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A normal-sized fresh avocado, weighing about 7 ounces, provides 3.4 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A tiny, half-ounce or tablespoon-sized serving of dried sunflower kernels contains over 3 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A half-ounce serving of pecans contains nearly 3 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A half-ounce serving of dehulled sesame seeds contains over 2.5 grams of linoleic acid [*].

An ounce of raw cashews contains 2.2 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A half-ounce serving of shelled pistachios contains slightly under 2 grams of linoleic acid [*].

About 100 grams of cooked corn kernels contain about 1.5 grams of linoleic acid [*].

The meat of a roasted chicken thigh contains just under 1.5 grams of linoleic acid per 3.5-ounce serving [*].

A half-ounce serving of dried chia seeds contains 0.83 grams of linoleic acid [*].

A small, 3.5-ounce serving of cooked, skinless chicken breast contains 0.6 grams of linoleic acid [*].

And an adult eating 2,000 calories per day would only require an average daily intake of about 2-3 grams of linoleic acid per day, total, to meet the estimated levels of 1-2% of daily overall calories required to prevent deficiency [*].

Not only that, but the majority of animal products, nuts, grains, and veggies also contain small amounts of linoleic acid — which add up quickly. Unless you happen to be severely undereating or eating an unnaturally narrow selection of foods, the chances are extremely low that you would ever develop a deficiency in the first place.

How Did Seed Oils Become Widespread in Our Diets if They’re Harmful?

According to a research group led by Christopher E. Ramsden, a principal investigator at the National Institutes of Health who focuses on the roles of lipid (oil and fat) oxidation in diseases, the foundational research claiming industrial seed oils are healthy was, itself, fatally flawed [*]:

Meta-analyses and studies generally failed to distinguish between the effects of omega-3 fats (which are widely known as heart-healthy) versus omega-6 fats, including linoleic acid, where many trials have administered or measured them together and, as a result, confounded the outcomes [*].

The authors of the Minnesota Coronary Experiment, the Sydney Diet Heart Study, and other early studies withheld data from the publication that contradicted their initial (favorable to seed oils) conclusions, and this has only come to light in the past 10-15 years [*,*]. Updated analysis of this "recovered data" by the Ramsden group shows significant harm from linoleic acid and seed oils that wasn't reported in the initial interpretations.

Unfavorable findings are regularly excluded from systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggesting the benefits to consuming seed oils [*].

In the words of John Ionnadis, the renowned Stanford professor and evidence-based medicine researcher,

“Simulations show that for most study designs and settings, it is more likely for a research claim to be false than true. Moreover, for many current scientific fields, claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.”[*]

It’s unfortunate that so many people who were only trying to make healthy choices were affected by these flawed research findings on industrial seed oils, but science isn’t perfect — rather, it’s self-correcting over time.

Now, after a century of increased chronic disease that’s likely due in part to industrial seed oils, we finally have enough information to make informed choices about this important issue.

Although it would be helpful to have more specific and rigorous trials to round out the dated, flawed, and incomplete data that’s currently available, it’s clear that at best, seed oils come with potential risks and offer no unique benefits, and at worst, could be driving major declines in public health around the world.

Recap: Are Seed Oils Toxic, Unsafe, or Both?

According to dozens of studies and papers looking at cells, animals, and humans, and consisting of tens of thousands of research subjects, there is very clear evidence that seed oils and linoleic acid can be toxic as well as unsafe in many circumstances.

And as we also covered, the questionable potential benefits of industrial seed oil consumption do not outweigh the evidence showing they’re toxic and unsafe, nor could they — toxicity and safety aren’t about “pros and cons.”

How Can You Eliminate Seed Oils from Your Diet?

Linoleic acid and omega-6 polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) are essential in your diet but only around 1-2% of your total daily calorie intake [*].

That’s in contrast to the typical linoleic acid intake levels of 6-10% or higher for the average person today, which are also associated with increased disease risk in studies [*,*].

So you don’t have to eat industrial seed oils at all to meet your dietary requirements. Also, by eliminating them, you’ll avoid oxidized linoleic acid and other harmful, inflammatory byproducts that are associated with so many health problems.

The good news is that seed oils aren’t especially tasty — they taste neutral at best or rancid at worst — so you won’t miss them.

The not-so-good news is that they're in most processed and packaged foods and most restaurant meals.

Depending on your lifestyle and personality, avoiding seed oils could involve some combination of learning to meal prep using healthy fat sources or asking a lot of questions at your favorite restaurants.

Aside from that, you’ll need to look for the usual suspects — canola, corn, cottonseed, grapeseed, peanut, rice bran, safflower, soybean, sunflower, and "vegetable" oil — on labels any time you’re shopping for prepared foods, and especially foods like salad dressings that tend to use seed oil as the primary ingredient.

Unfortunately, increased levels of linoleic acid can also show up in certain animal products (including pork, poultry, fish, and eggs) from animals fed grains, soybeans, and cheap feed containing industrial seed oils [*].

Though these animal products are not as significant a source as eating industrial seed oils, shifting any consumption of animal products to grass-fed, pastured, and wild-caught when possible is another step to consider in reducing your linoleic acid intake.

What Should You Eat Instead of Seed Oils?

There is no “perfect” oil or fat for everyone — like all foods and nutrients, our bodies do best with a balanced and diverse intake. In general, however, it’s best to steer clear of any fat that’s high in easily-oxidized omega-6 fatty acids.

Other factors to keep in mind include:

Look for fats and oils with high smoke points for cooking.

Make sure that your fats and oils are higher in heart-healthy monounsaturated fats.

Include fats that work with your current diet and lifestyle. For instance, vegans might want to stick with real, high-quality olive oil while Paleo folks might opt for grass-fed butter or ghee.

Opt for fats and oils that don’t decimate the rainforest or otherwise harm the environment. For instance, vegetable oil crops take up more land than all fruits, vegetables, legumes (pulses), nuts, roots and tubers combined, leading to record rates of deforestation [*,*].

The main goal is to reduce the amount of seed oils you’re consuming as quickly as possible so your body can begin replacing linoleic acid at the cellular level with healthier, more stable fats from your diet. Of course, preparing more meals at home and asking more questions about cooking oils at your favorite restaurants will help, too.

Cultured Oil is also an option — a heat-stable, low-linoleic acid cooking oil that you can use for everything. You can read more about Cultured Oil here.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Seed Oil Toxicity and Safety

Is Vegetable Oil the Same as Seed Oil?

No, they’re not the same. Vegetable oils are any oils or fats derived from crops, including seeds. This broad category includes all crop-based oils, but there aren’t any real vegetables involved in making seed oils.

Instead, industrial seed oils are made by using pressure, solvents, and high heat to extract minuscule amounts of oil from seeds. As a result, they're highly refined and are also high in the inflammatory omega-6 fatty acid, linoleic acid.

Keep in mind that while all seed oils are technically vegetable oils, not all vegetable oils are seed oils.

What Is So Bad About Seed Oils?

In vitro studies, animal studies, human clinical trials, and observational studies show that industrial seed oils are highly reactive and unstable. They contain inflammatory linoleic acid, which is associated with heart disease, cancer, dementia, and other health problems. Seed oils are also terrible for the environment. In fact, two of the top three drivers of global deforestation are vegetable oil crops [*].

What Are the Worst Seed Oils for Your Health?

Canola (rapeseed) oil, corn oil, cottonseed oil, grapeseed oil, rice bran oil, soybean oil, safflower oil, and sunflower oil are the eight worst seed oils you may want to avoid. Average consumption has increased 20 times in the past hundred years, which correlates to increased rates of obesity, cancer, and heart disease [*,*].

Physician and biochemist Dr. Cate Shanahan originally coined the term “the hateful eight” to refer to these industrial seed oils.

What's the Worst Oil to Cook With?

All industrial seed oils are bad for cooking because omega-6 fatty acids, especially linoleic acid, create harmful byproducts when they’re heated. These deleterious effects occur within minutes of being heated and compound when oils are reheated. Safflower, grapeseed, and sunflower oil contain the most linoleic acid among seed oils.

What Oils Should You Avoid?

Canola oil, corn oil, cottonseed oil, grapeseed oil, peanut oil, rice bran oil, soybean oil, safflower oil, and sunflower oil are industrial seed oils that you may want to avoid for health reasons. Also, beware of products that contain "vegetable oil" or "vegetable oil blend," which are alternative terms for seed oils.

What Should You Use Instead?

Vegetable oils like avocado, coconut, and olive oil are known for their slightly lower linoleic acid content and decent smoke points. However, each of these comes with compromises.

Cultured Oil, on the other hand, is a cooking oil without many compromises. High in heart-healthy and heat-stable monounsaturated fat, Cultured Oil has a sky-high smoke point of 485°F and a clean neutral taste. It also has one of the lowest linoleic acid levels on the market, less than 3%.

Unlike coconut oil or palm oil, you can use it for everything from salad dressings (that won't clump in the fridge) to sauteing and deep frying.

Made by fermentation, Cultured Oil uses 85% less land than canola oil, emits 86% less CO2 than soybean oil, and requires 99% less water than olive oil, making it the natural choice when it comes to sustainability.