WRITTEN BY: Zero Acre Farms

Highlights

Fermentation has been used for thousands of years to transform one type of food into another — it’s the oldest culinary art after fire.

Today, an estimated one-third of all foods we eat are fermented.

Just as there are microbial cultures that make bread, beer, cheese, yogurt, and kombucha, there are also cultures that make oil.

Fermentation can be used not only to create some of the healthiest and most delicious foods on the planet but also to make them more sustainable.

Introduction

Humans have used the culinary art of fermentation for thousands of years to transform one type of food into another. In fact, fermentation is the oldest culinary tradition after fire. By marrying food with microorganisms, fermentation is what makes some of our favorite foods and drinks possible, including bread, beer, cheese, yogurt, wine, kombucha, sauerkraut, kimchi, pickles, coffee, and even chocolate.

Fermentation is also the process that makes Cultured Oil possible.

To understand how the magic of fermentation is used to produce bread, beer, cheese, and Cultured Oil, it's helpful to first understand what fermentation is.

What is Fermentation?

Fermentation describes the process of microbial communities, or "cultures," converting natural sugars like those found in wheat, barley, milk, and grapes into entirely new foods like bread, beer, yogurt, and wine. The microorganisms that make up a culture include bacteria, microalgae, yeast, and other fungi.

Fermentation is a natural process that humans have harnessed for millennia to create a number of the foods and drinks we love today.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Bread

Sourdough is one of the oldest forms of grain fermentation, wherein live cultures transform the sugars in wheat flour into carbon dioxide gas. The carbon dioxide causes the bread to rise, and chains of gluten (a wheat protein) hold the gas in, creating those tiny holes that form sourdough's airy texture. Other microorganisms in the culture also feed on the wheat sugars to produce lactic acid — putting the "sour" into sourdough.

Sourdough cultures, called “starters” or “starter cultures,” are so prized for their unique microbial cultures that they’re often kept alive to use over and over in different batches of bread and are even passed down between family members.

Beer

From the lightest lager to the funkiest sour, every beer is fermented, and every fermentation starts with a microbial culture. In the case of beer, microorganisms feed on the sugars in malted barley — a grain that looks a lot like wheat — and convert (ferment) those sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

The alcohol, of course, is the main attraction of beer, and the carbon dioxide gas gives beer its subtle carbonation.

Before fermentation, hops (flowers of the hop plant and a member of the hemp family) are added to the malted barley. Hops contain acids and oils that give beer its bitterness, aroma, and distinctive flavor.

Cheese

Like many fermented foods, cheese was created out of a necessity to preserve milk for long periods of time before the advent of refrigeration.

Unlike bread and beer, which are products of fermented plant sugars, cheese is a product of fermented animal sugars — those naturally present in the milk of cows, goats, and sheep.

In the cheesemaking process, live cultures ferment milk sugars (lactose) to produce lactic acid. The longer the fermentation, the less sugar remains. For instance, soft cheeses like mozzarella and brie result from relatively short fermentation periods of only a few days and still contain unfermented lactose.

Many hard cheeses, on the other hand, ferment for months. During that time, microorganisms in the cheese continue to ferment the milk sugars, and by the time a hard cheese like cheddar or Parmesan is ready to eat, there’s hardly any lactose remaining at all.

Yogurt

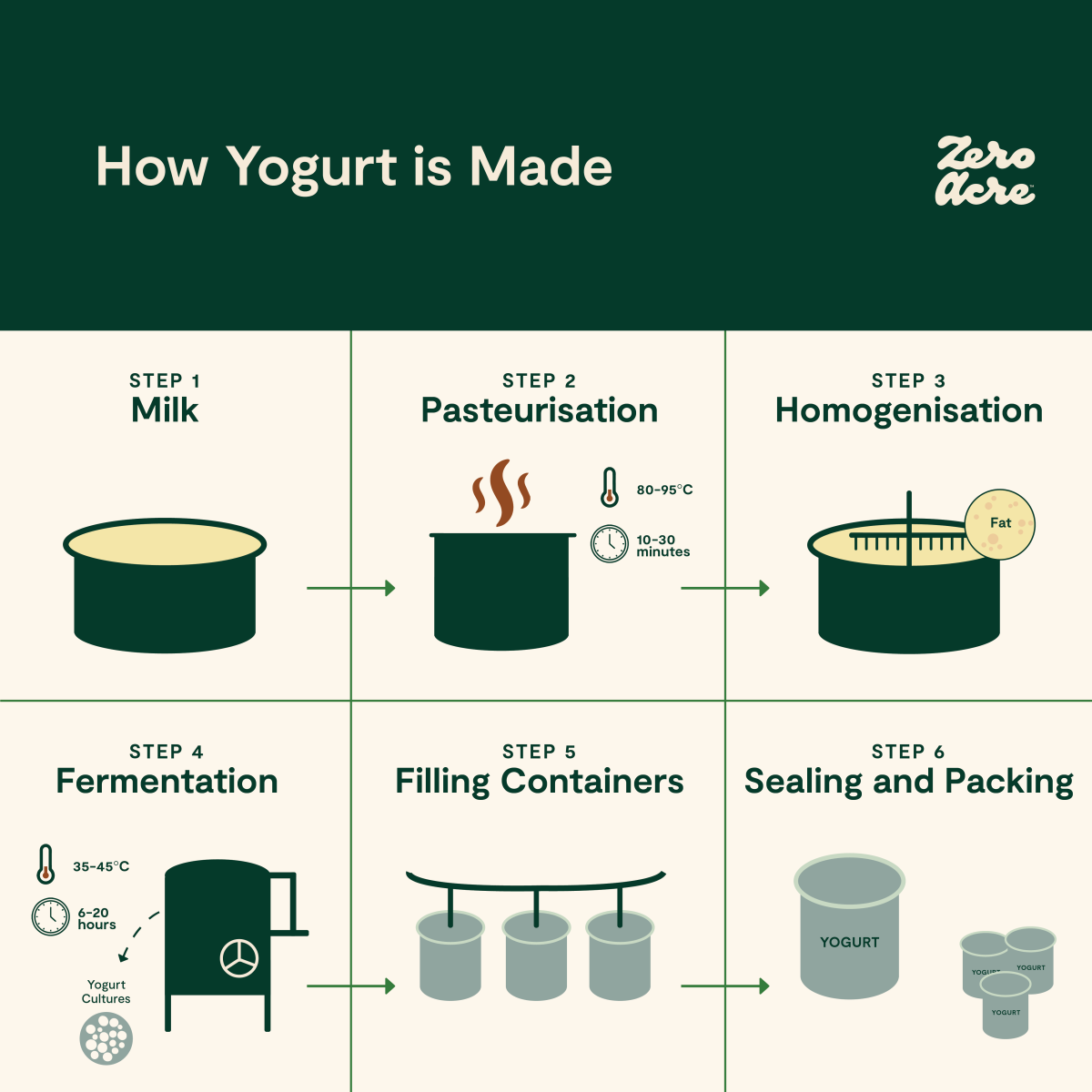

Yogurt is another popular dairy product made possible by fermentation, and the basic process of making yogurt hasn’t changed much in 10,000 years.

To make yogurt, a starter culture is added to milk, and after a few hours or days, microorganisms in the culture ferment the milk sugar to form lactic acid, which gives yogurt its signature tang. Once the fermenting milk becomes sufficiently acidic, casein proteins begin to clump together, thickening the now tangy milk into a substance we call yogurt.

Kombucha, Wine, Sauerkraut, Kimchi, Pickles, Tempeh, Ketchup, Coffee, Chocolate, and Cows…

Bread, beer, cheese, and yogurt are just the tip of the fermentation iceberg. Hundreds of other foods have fermentation to thank for their unique properties.

Fermentation has been used since antiquity to create desirable flavors, naturally preserve foods, and transform sugary plants into prized health foods like kombucha, sauerkraut, kimchi, and dark chocolate.

Kombucha, for example, is the result of mixing sugar, black tea, and a starter culture, also known as a SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture Of Bacteria and Yeast). After a couple of weeks, the culture ferments nearly all of the sugar into acetic acid (vinegar), a tiny amount of alcohol, and carbon dioxide to create a slightly acidic, sweet, and bubbly beverage.

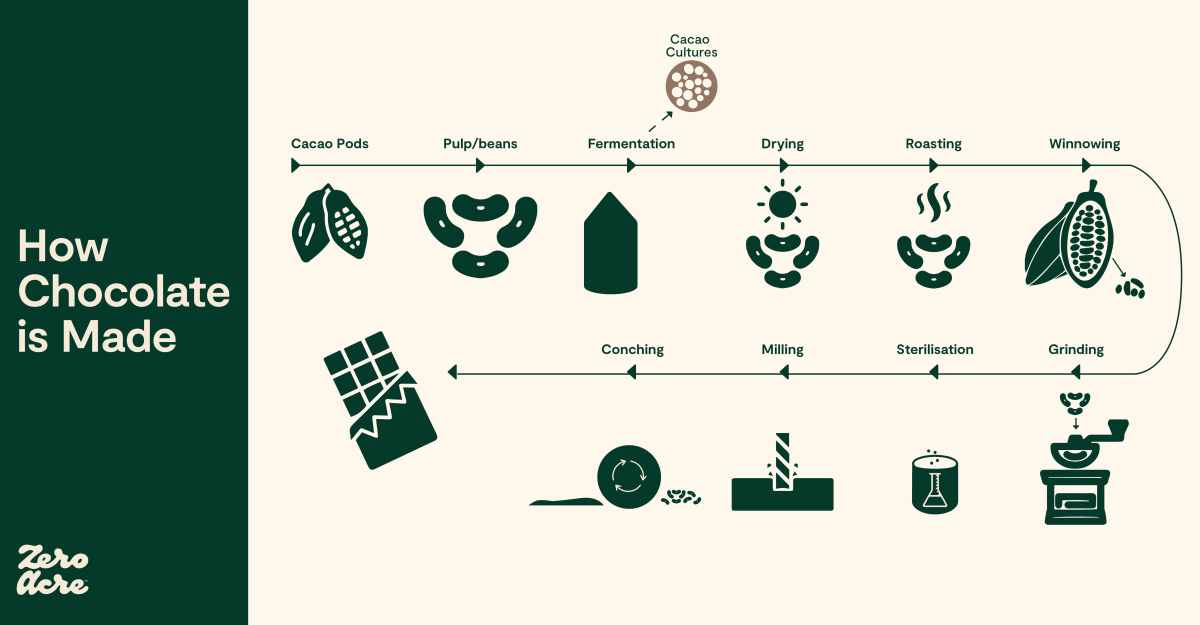

Fermentation is also the secret ingredient behind one of the world’s most beloved foods: chocolate. In one of the first steps in chocolate making, microorganisms ferment and transform bitter, otherwise tasteless cacao seeds into the rich flavors we associate with chocolate [*].

Mammals even have fermentation to thank for the ability to transform certain sugars, carbohydrates, and fibers into digestible nutrients.

When ruminant animals such as cows, goats, and sheep consume plants (typically grasses), the microbial cultures in their guts (aka, the gut microbiome) break down the plant sugars and fibers via fermentation.

So, fermentation is not only responsible for the culturing of milk into yogurt, cheese, and other fermented dairy products; it's also the first step in transforming grass into what eventually becomes milk.

Even closer to home, fermentation in our bodies is the reason that fiber is typically considered an important part of a healthy diet. Microorganisms in the human digestive tract ferment dietary fiber into a variety of outputs, including short-chain fatty acids that nourish our guts and have been associated with a number of health benefits, from immune function to mental health.

Cultured Oil

Just as there are microbial cultures that make bread, beer, cheese, yogurt, and kombucha, there are also cultures that make oil.

Instead of producing the carbon dioxide that leavens bread and carbonates beer, or the lactic acid that gives sourdough and yogurt their distinctive tang, an oil culture ferments natural sugars into healthy fats.

Ten thousand years ago, there wasn’t a name for the thick, tangy culture of milk we now call yogurt or the alcoholic byproduct of fermented barley and hops we now call beer. Similarly, until now, there wasn’t a name to describe the product of a fermented oil culture, so we came up with the most straightforward name we could think of: Cultured Oil.

Just like our other favorite fermented foods, Cultured Oil is made by feeding natural sugars to a culture and letting the magic happen. Here’s how it works:

It all starts with an oil culture (a community of microorganisms cultivated specifically for making healthy fats).

Next, the culture is fed sugar from non-GMO, perennial sugarcane.

Over the course of a few days, microorganisms in the culture convert (or ferment) this sugar into oils or fats. Some oil cultures produce more liquid oils, while others produce more solid fats.

To harvest, the culture is pressed and the oil is released.

Finally, the pressed oil is separated and filtered, resulting in Cultured Oil.

While the first food fermentations thousands of years ago were probably accidental — one of our ancient ancestors leaving wet honey out until it produced alcoholic mead, or leaving grapes and water in a bucket until it created wine — as time has progressed, fermentation has become more and more intentional.

Today, we can harness the magic of fermentation to not only create some of the healthiest and most delicious foods on the planet, but also to make them more sustainable.

For instance, Cultured Oil boasts even more heart-healthy monounsaturated fats than olive oil, and is low in inflammatory omega-6 linoleic acid. And by replacing just 5% of destructive vegetable oil with Cultured Oil in the U.S. alone, we would:

Save 3.1 million acres of land every year

Save 56.9 billion gallons of fresh water every year

Avoid 3.6 million tons of CO2 emissions every year

Preserve 5.1 billion square feet of biodiverse rainforest every year

Fermentation dates back well over 10,000 years. Today, an estimated one-third of all foods we eat are fermented [*], and populations around the globe rely on the microbial cultures that make fermentation possible. It’s no coincidence that the word “culture,” used to describe “the manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively,” is the same word used to describe communities of microorganisms that give us some of our favorite foods.

Like a company culture, organizational culture, or societal culture, the cultures that enable fermentation bring us together through breaking bread, cheers-ing beers, fondue-ing cheese, sharing chocolates, and now, through drizzling, sizzling, dressing, and searing our favorite foods with Cultured Oil.

Watch our video to learn more about how Cultured Oil is made.